A Brief Overview of Czech Fashion History

ThE First Czechoslovak Republic: The golden Age

1918–1924: Post WW1 Rebuilding and Feminist Foundations

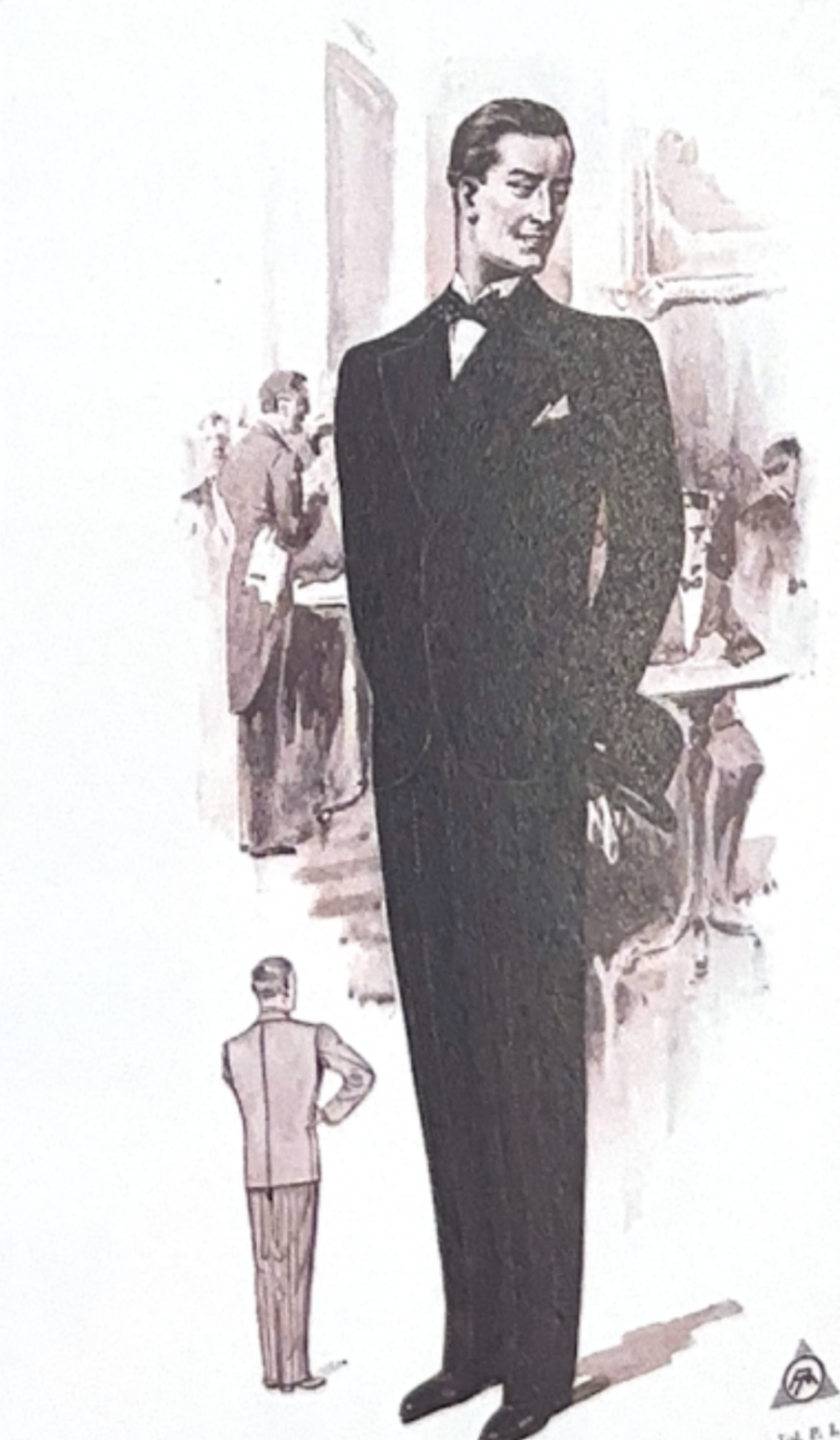

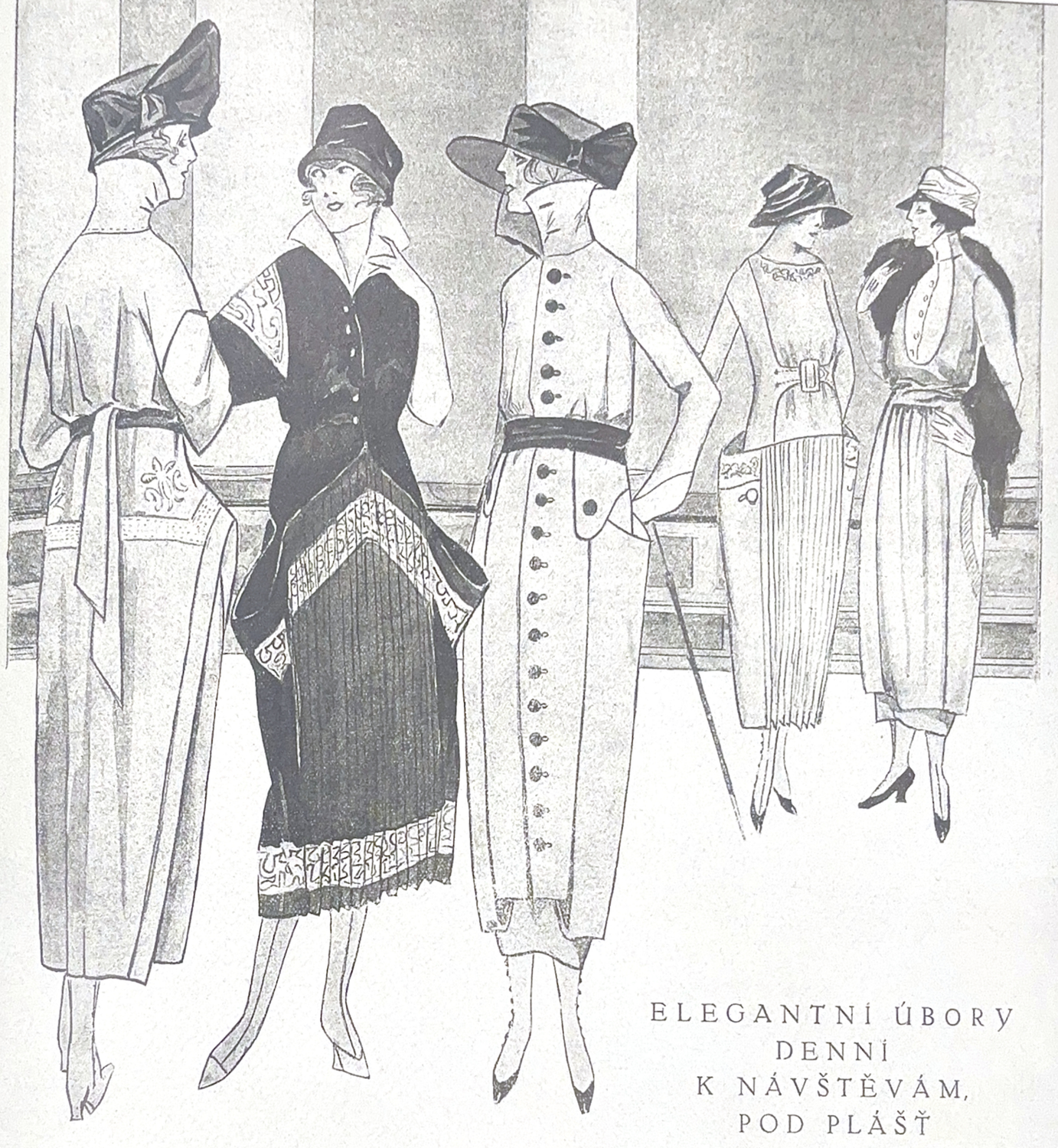

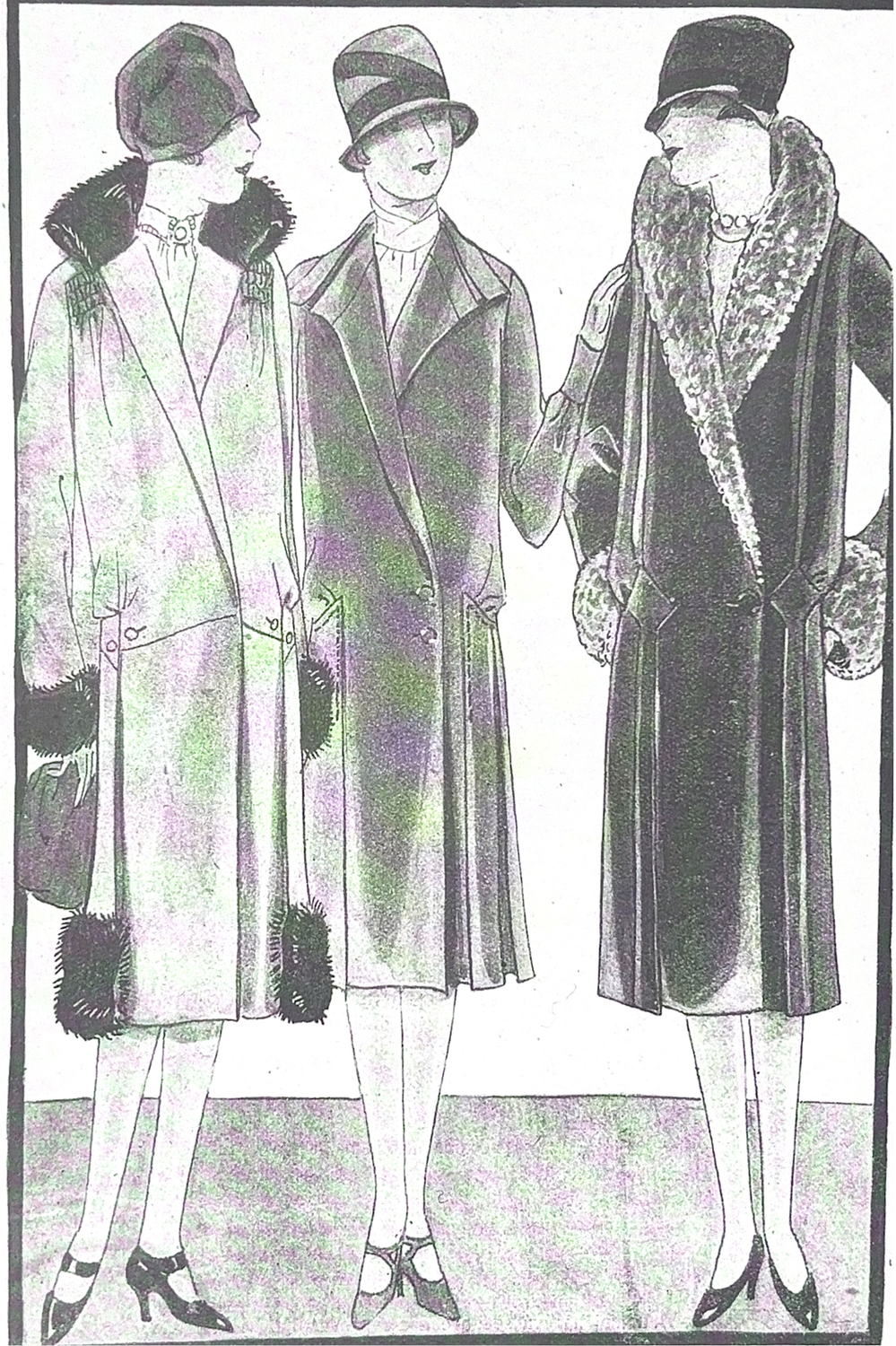

Following independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Czechoslovak women gained political rights and university access. Their newfound independence was mirrored in fashion through the rejection of Austro-Hungarian styles and the embrace of Parisian trends. Domestic production and home sewing were common due to postwar austerity, but women used barrel-shaped dresses, military motifs, and luxe fabrics to develop modern identities. The Svěraz movement fused national pride with folk styles, as it quickly rose in popularity to attempt to create a uniquely Czech way of dressing. Furs were used on both formal and walking wear. Long furs, like fox and monkey, were used in formal/evening wear, while shorter furs were reserved for collars, cuffs, and overcoats. There were 2 distinct silhouettes for evening wear. Long, narrow sheath dresses with low waist lines and tight bodices, with a drop waist and a wide crinoline skirt adorned with flounces and pleats. Fashion became a feminist tool, empowering, modern, and self-made, a quiet revolution woven through the seams of everyday life.

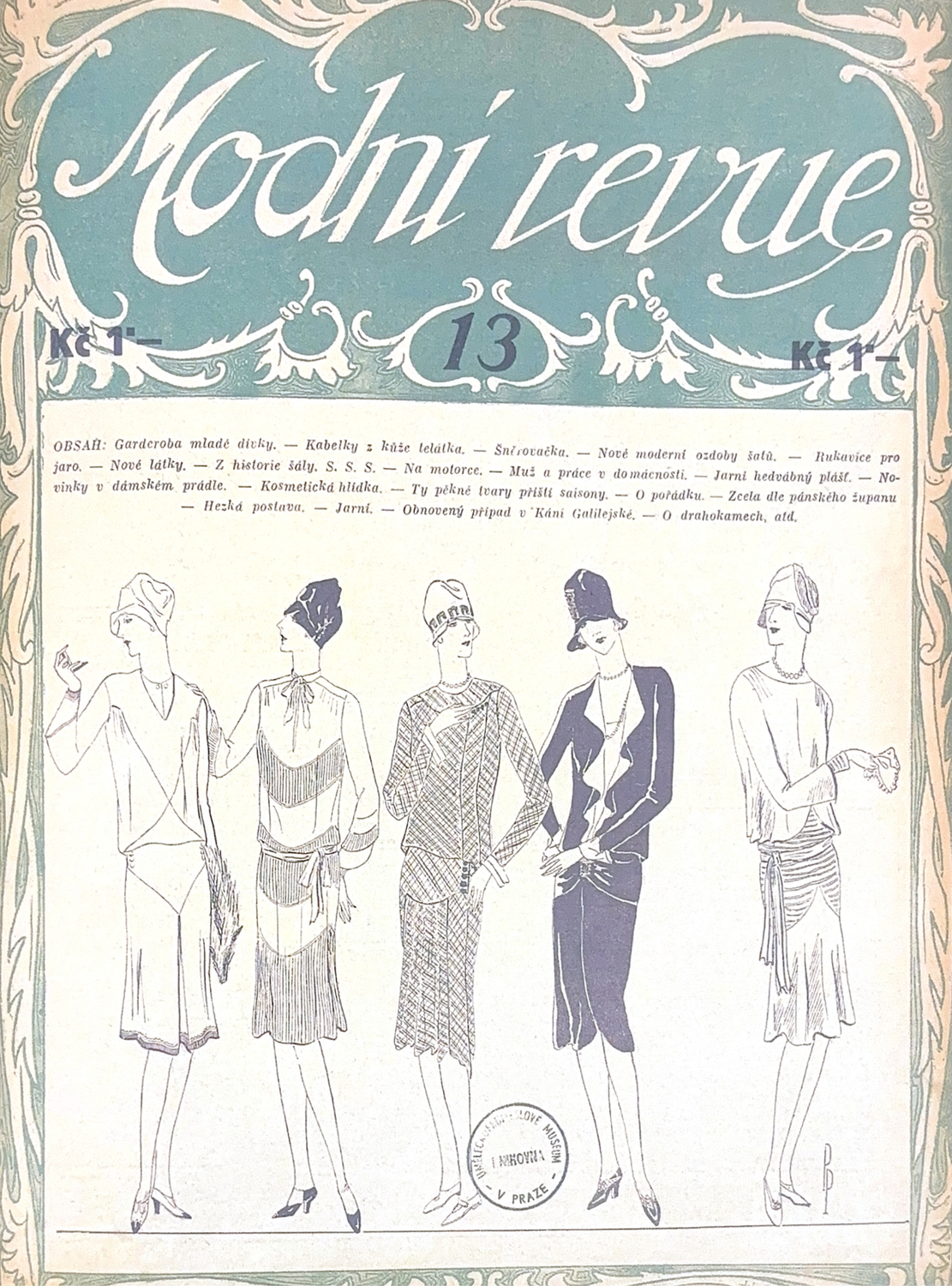

1925–1928: Sporty Modernity and Shifting Ideals

As the economy stabilized, fashion shifted toward sporty, pragmatic clothing. Women adopted jersey tops, walking skirts, and tailored suits for mobility in the workplace. It became more common to see suits made of multiple kinds of fabric, which rose in popularity, and they would be tied together by using the same decorations all over the garments or by interfacing the fabrics to decorate the other side. More formal suits had the same fabric for the skirt and overcoat. In 1928, a backlash against masculine silhouettes emerged, prompting a return to Czech femininity. This style tug-of-war revealed deeper tensions: between French cosmopolitanism and national identity, between gendered expectations and personal expression. The fashion press debated femininity and modernity, making style itself a battleground for cultural direction

1929–1936: Femininity Revived Amid Crisis

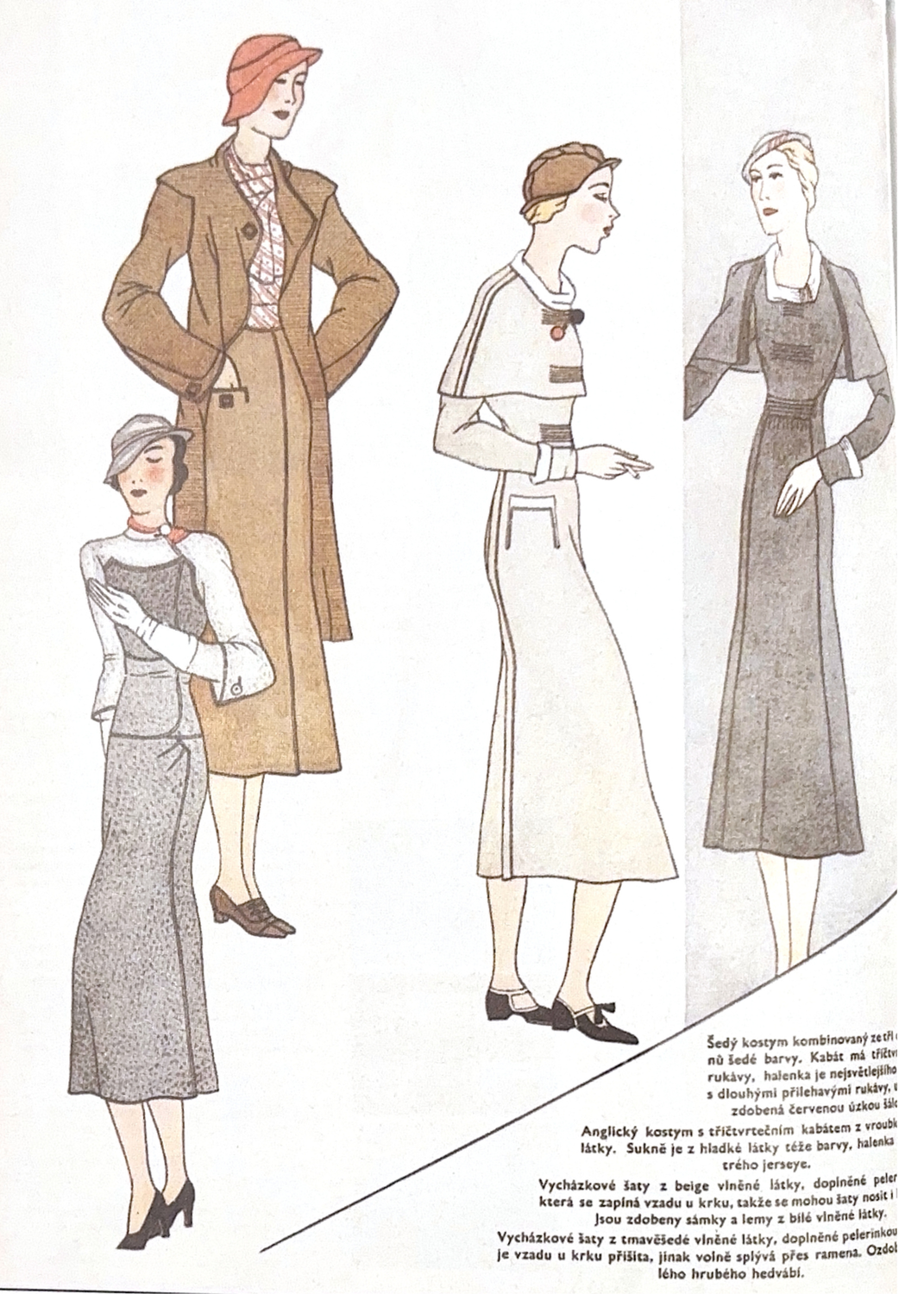

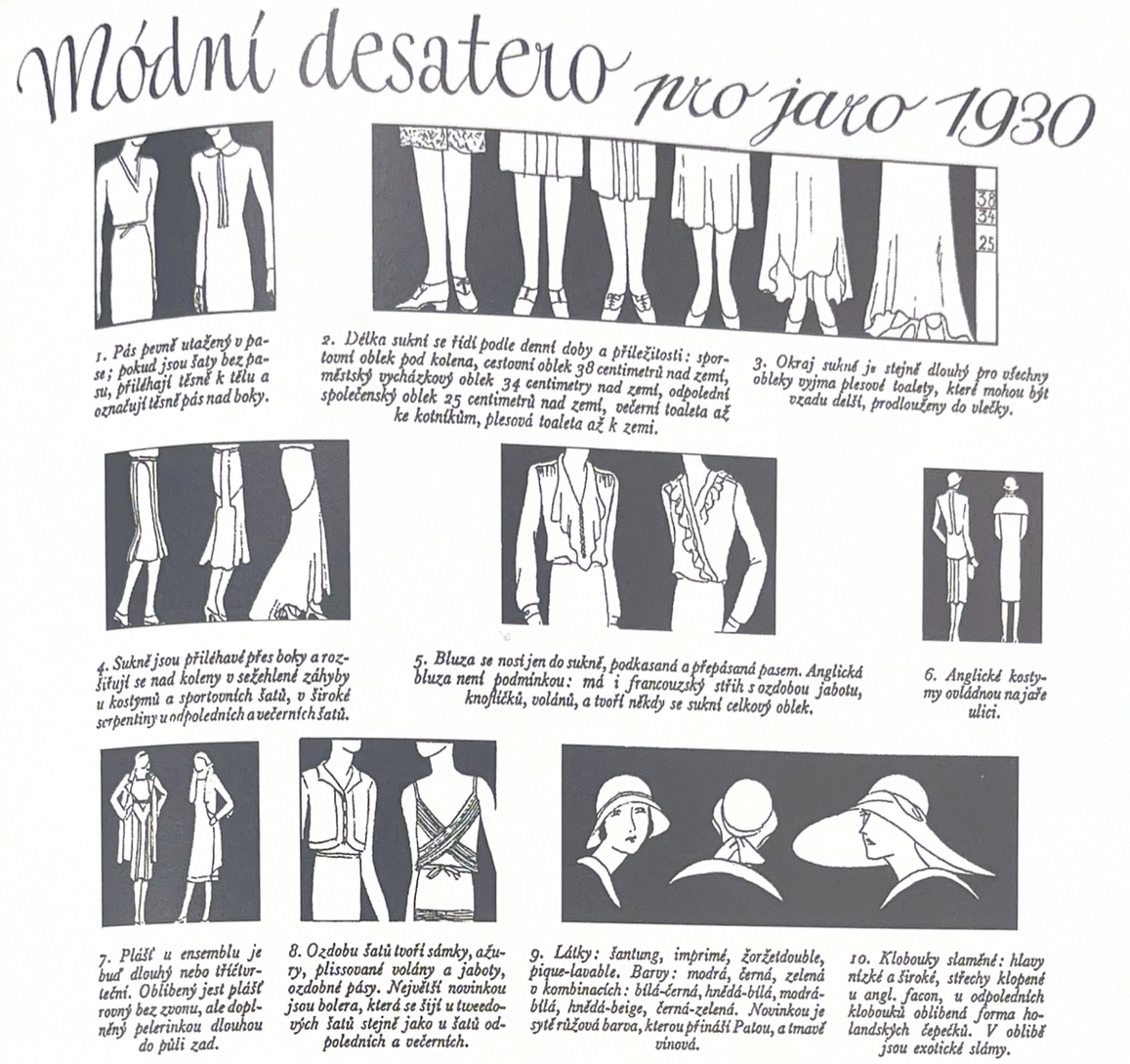

An economic downturn triggered a return to modest, traditionally feminine silhouettes, longer skirts, fitted waists, and romantic headwear. Yet this revival was not passive. Women’s fashion still emphasized autonomy, with shaped bras, garter belts, and leisurewear blending form with function. Critics like Helena Sedláková called out growing modesty in sportswear, defending style as self-expression. Amid economic strain, fashion served as both armor and escape, refusing feminine erasure while signaling resilience through fabric innovation and tailored grace. By 1930 the boyish figure had fallen out of fashion and slim, slightly athletic builds rose in popularity.

1937–1939: Prewar Elegance Meets Subtle Defiance

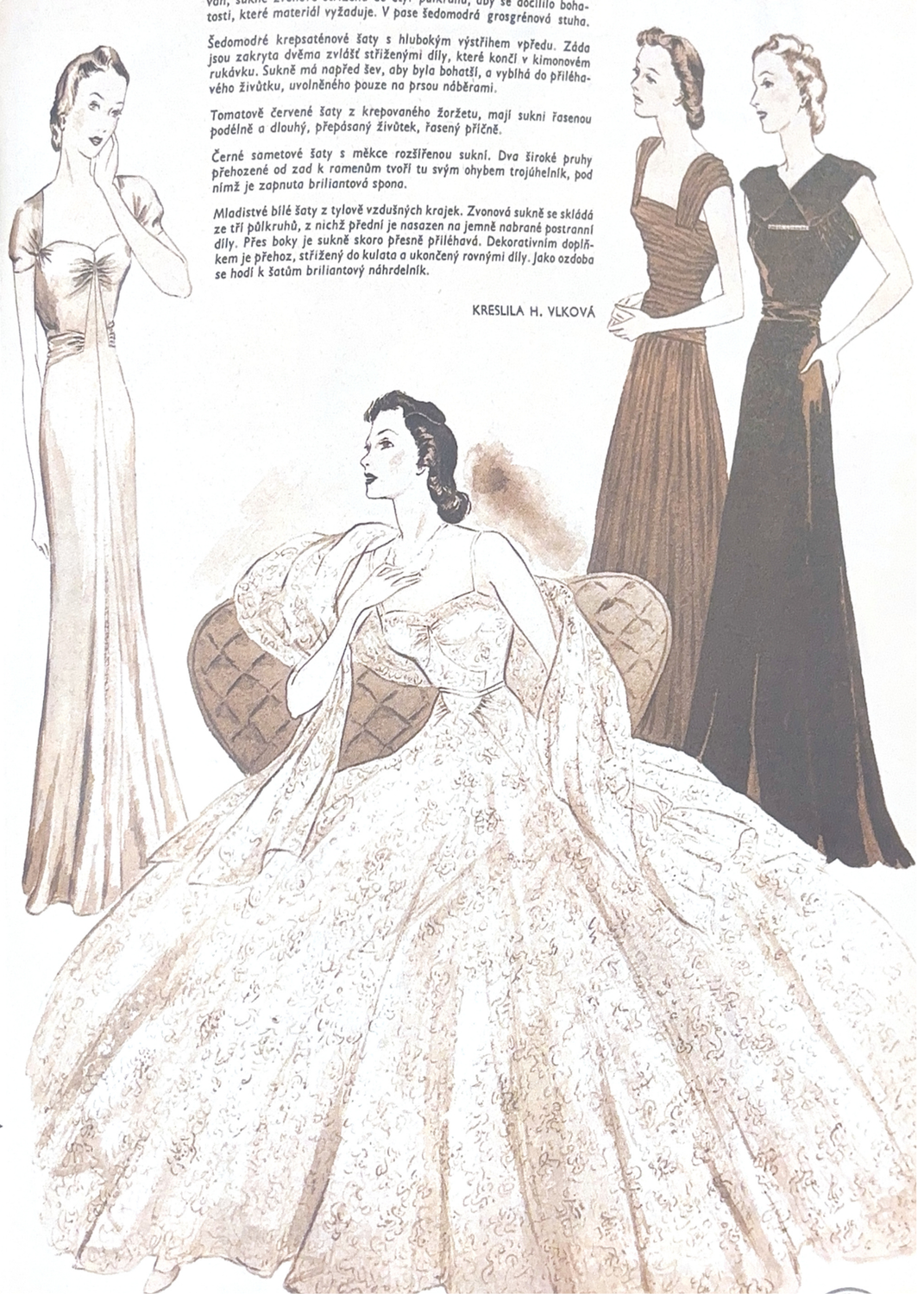

As World War II loomed, fashion embraced “natural line” silhouettes: full busts, slim waists, curved hips—balancing practicality with optimism. While militarization affected industry, many brands clung to elegance, resisting the uniformity to come. Czech brands like Sochor Fabric Co. subtly prepared for wartime needs, yet continued promoting refined styles. In a period of creeping authoritarianism, fashion quietly insisted on beauty and identity. Garments were not radical, but in their softness and tailored confidence, they offered resistance to the rising tide of fascism

1939–1945: Wartime Scarcity and Fashion as Resistance

Under Nazi occupation, fashion became survival. Rationing forced simplicity, but embroidery and repurposed fabrics offered quiet rebellion. Designers like Hana Podolská, known as the "Czech Coco Chanel") continued to operate, but under severe restrictions, with conservative and pragmatic designs. She refused to collaborate with the Nazis and was eventually punished postwar for operating during the occupation—despite avoiding direct collaboration. Baťa, a shoe company, continued operating under German control, producing standardized shoes for civilians and the military. They cooperated as a means of preventing further conflict, and they relocated all of their vulnerable employees (Jewish people, Romani people, etc.) and resisted manufacturing for Germany for as long as possible, but ultimately, the owners were exiled to the USA, even after fighting in the war in London.

Socialist Czechoslovakia

1948-60:

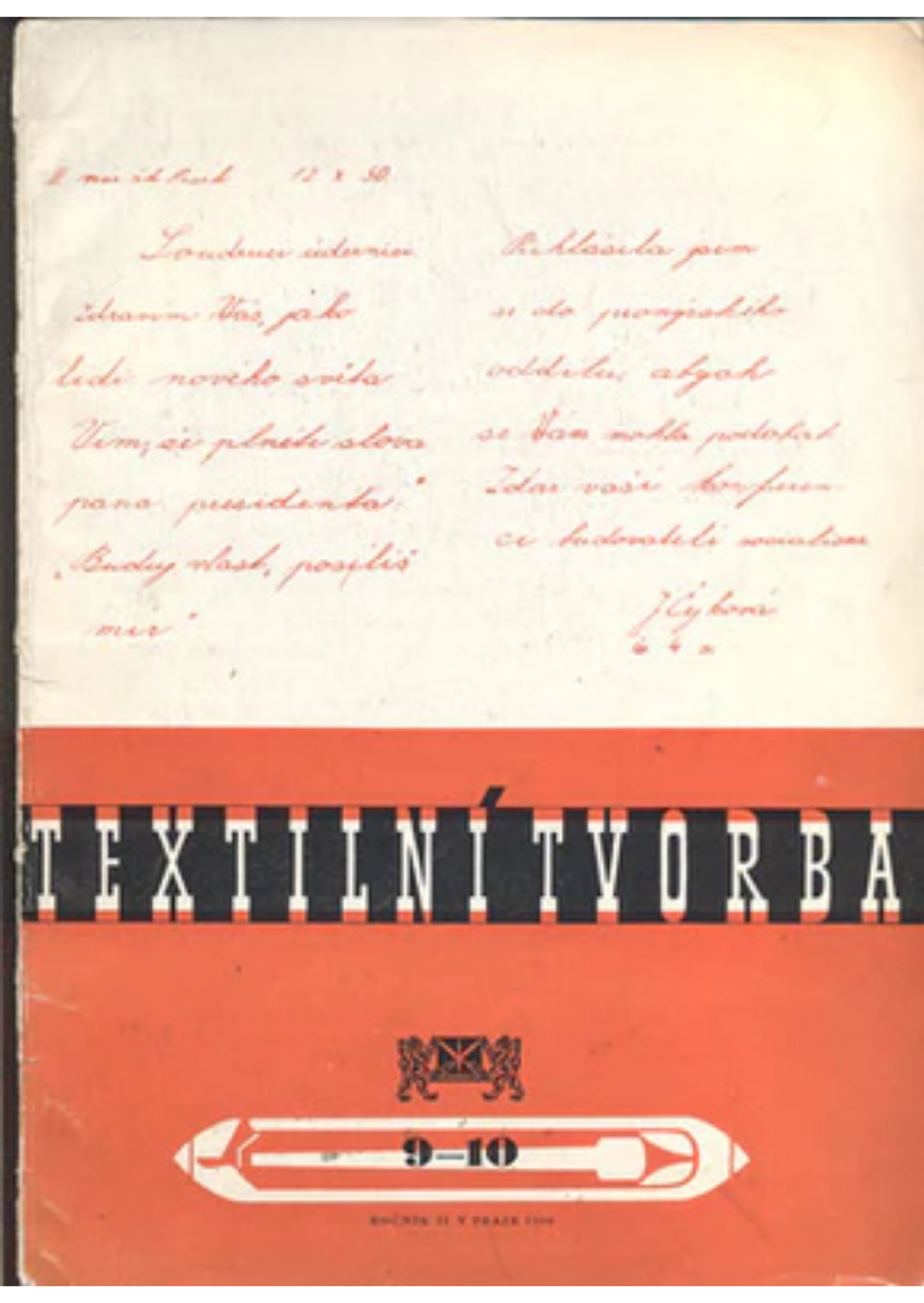

Post 1948, Czechoslovakia nationalized its textile and clothing industry; as a result, fashion houses based on the soviet union’s fashion and textile model were set up to coordinate the clothing industry and design. Tekstilnà Tvorba (Textile Creation) was established in Czechoslovakia in 1949 by a decree of the Minister of Industry. Zdeňka Fuchsová (1903–88), who, as a pre-war fashion designer from the leading Prague fashion salon Rosenbaum, had made regular visits to Paris in the interwar years. Thus, her technical expertise was a valuable asset for the newly founded central fashion institute. In 1958, the Czechoslovak Tekstilnà Tvorba became Ústav Bytové a Odĕvni Kultury (Institute of Housing and Dress Culture, ÚBOK). The change of name announced much deeper transformations, bringing the whole field of living and lifestyle activities under the control of ÚBOK.

Socialist Realism is the cultural doctrine of many communist states that were politically aligned with the soviet union. This impacted fashion by creating nearly indistinguishable clothing for men and women within genders themselves; there was even less variation. Magazines like Zena a Moda (Woman and Fashion) and Vlasta began to come into existence. They were used to promote the Communist Party’s ideal way for women to dress. In a continued attempt to establish a socialist style that would be functional, but modest, feminine, and fashionable, annual dress contests between the socialist countries started in 1950. The initial idea for dress contests was born in Czechoslovakia, the natural leader in the field of clothing due to its highly developed pre-war traditions. Only Czechoslovakia and East Germany took part in the first two annual dress contests, and, with a presentation organized by Tekstilnà Tvorba, Czechoslovakia won on both occasions, presenting an exceptionally superior fashion show at the second contest held in Leipzig.

1960-79:

After merging several department stores, private fashion salons, and Darex, DĹŻm MĂłdy (House of Fashion) was established in Prague in 1966. They produced small-batch, fashionable clothing meant for middle-class consumers and professionals. Clothing design in Czechoslovakia began incorporating Western fashion trends, though filtered through socialist ideals of modesty and simplicity. After the failed political liberalization of 1968, a period of normalization began. Fashion consumption became a substitute for political freedom: consumer goods were offered to appease the population while repressing political dissent. The regime re-legitimized fashion consumption (especially among women), as long as it remained politically quiet and ideologically appropriate. By now, materials were scarce.

Czechoslovak middle-class women sought better-quality clothing via do-it-yourself (DIY) fashion. They also sought increased availability of paper patterns and do-it-yourself instructions in women’s magazines. Sewing at home or using a private seamstress became widespread due to the lack of quality mass-produced clothing.

1980-1989:

In Czechoslovakia during the socialist era, jeans were a rare and highly coveted item, unlike in the U.S. or Western Europe, where they were easily accessible. Beginning in the 1960s, jeans could only be purchased from Tuzex, a network of state-run stores that required hard-to-obtain vouchers for foreign goods. These vouchers were only legally attainable by high-ranking communist party members. People often had to wait in long lines to buy them, much like other scarce commodities such as bananas and sewing patterns. There was a big black market in trading currency and Tuzex vouchers in the 1980s. Though initially viewed by authorities as a decadent symbol of Western defiance and inappropriate for everyday wear, jeans gradually became a popular fashion item, especially by the 1980s. Slang terms for jeans included "rifle," named after the Italian brand Rifle, and "texasky," referencing the U.S. state of Texas; the official Czech word was "dĹľĂny." This growing association of jeans as something uniquely American and really Texas, much to the government's dismay, contributed to the notion that jeans symbolized renaissance and freedom. The Czech government even tried to make its own jeans brand, but they never grew as popular as foreign jeans.

Meanwhile, the underground punk scene exploded as a direct challenge to state authority. Punks risked arrest and psychiatric institutionalization for wearing leather, spikes, and torn clothes. Simultaneously, New Wave fused avant-garde fashion with subversive lyrics and aesthetics. Despite state surveillance and censorship, bands like F.P.B. and Visacà Zámek created an oppositional culture. DIY fashion, thrifted Western styles, and personalized outfits made the body a political canvas. In the face of repression, fashion in the 1980s became more than style; it was a coded language of refusal, creativity, and survival.

1990s-Now

Czech fashion Industry

By the mid-1990s, Czech fashion had become globalized. As people gained more and more access to the fashions of the West, the distinctions between what is considered Czech fashion and European fashion diminished. The longest prevailing distinction between Czech fashion and global fashion is, of course, traditional folkwear, which isn’t regularly worn anymore. A few Czech brands have broken into the global market, as well as a few notable fashion schools.

In the early days of snowboarding, the sport was a fresh, rebellious break from traditional team sports, embraced by a small crew riding the mountains around Rock Creek, Canada. The name Horsefeathers, meaning “nonsense,” came from co-founder Stew Carlson’s grandmother’s saying, and became an inside joke among the Czech-Canadian snowboarders at BCSS high school. After meeting in Europe, Hanuš and Pavel KubĂÄŤek launched Horsefeathers in 1993 with just 50 t-shirts and 200 stickers, eventually moving the company to the Czech Republic.

Founded in 1885, the Prague School of Applied Arts (UMPRUM) emerged when decoration was integral to everyday objects, building a library focused on decorative art theory and model studies. Initially offering women limited access through specialized schools for drawing, embroidery, and flower painting, all disciplines were opened to them only after 1918. UMPRUM gained university status in 1946, expanded in the 1960s toward freer artistic expression, and added a renowned industrial design studio in ZlĂn under ZdenÄ›k Kovář. The 1970s brought a creative decline under politically conformist leadership, though figures like scenographer Josef Svoboda earned international recognition. The school played a role in the 1989 Velvet Revolution, with its students designing the Civic Forum logo.

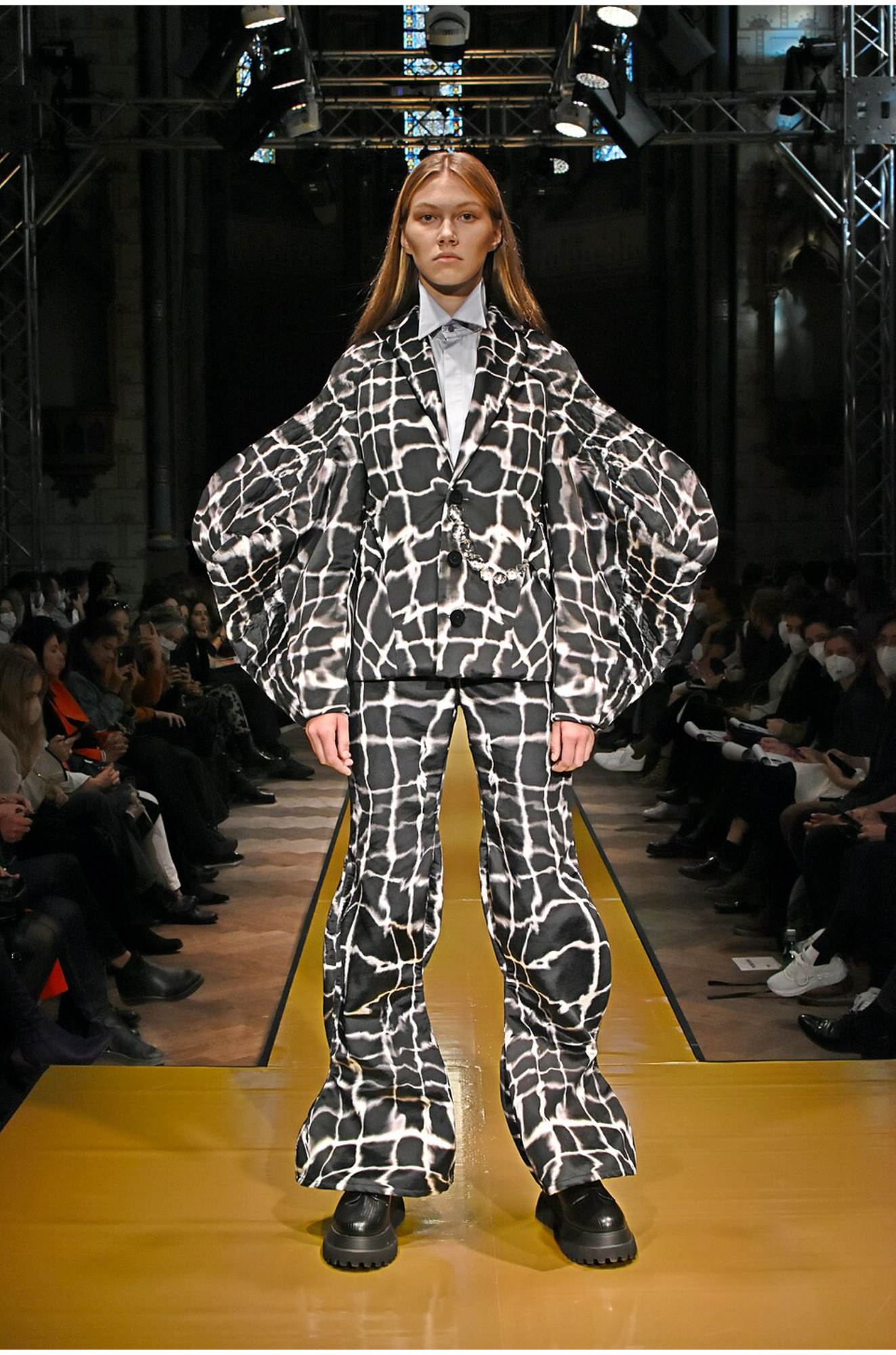

Mercedes-Benz Prague Fashion Week

The Mercedes-Benz Prague Fashion Week (MBPFW) stands as the premier international fashion event in the Czech Republic, showcasing meticulously selected Czech and Slovak designers. Established to highlight both emerging and established talent, MBPFW bridges fashion, art, and business, drawing a global audience. Its roots trace back to mid-20th-century initiatives like the socialist-era dress contests, where Czechoslovakia led in functional yet stylish design. Today, MBPFW celebrates Czechia’s unique fusion of tradition and modernity, with designers like LibÄ›na Rochová and Zuzana KubĂÄŤková blending haute couture craftsmanship with contemporary trends.

Bibliography

“90s Rifle Jeans| Vintage Deadstock Blue Pants| Super Slim Denim Made in Italy| Rifle 182 Pant Size 7/8.” Fashion and Fables, 2020, www.fashionandfables.com/products/90s-rifle-jeans-vintage-deadstock-blue-72056?srsltid=AfmBOoqWVtsXP_CFNluQ_O8yqyvyhRq9nUcHadDyX_pPWupD3e4BiXLS. Accessed 3 Sept. 2025.

“Album Representantů Všech Oborů Veřejného Života Československého - 1927 - Hana Podolská.png - Wikimedia Commons.” Wikimedia.org, 1927, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Album_representant%C5%AF_v%C5%A1ech_obor%C5%AF_ve%C5%99ejn%C3%A9ho_%C5%BEivota_%C4%8Deskoslovensk%C3%A9ho_-_1927_-_Hana_Podolsk%C3%A1.png. Accessed 3 Sept. 2025.

Bajić, Pavle. “The Kroj - a Connection to Czech Heritage Â鶹ľ«Ć· -.” , 26 Feb. 2021, www.czechcenter.org/blog/2021/1/11/the-kroj.

Bartlett, Djurdja. “Socialist Dandies International: East Europe, 1946–59.” Fashion Theory, vol. 17, no. 3, June 2013, pp. 249–298, ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/id/eprint/5771/6/SOC_DANDIES_12_March_13_DB.pdf, https://doi.org/10.2752/175174113x13597248661701. Accessed 3 Sept. 2025.

---. “The Totalitarian State and Fashion in the Twentieth Century.” Cambridge University Press EBooks, 4 Aug. 2023, pp. 890–933, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108862349.007. Accessed 3 Sept. 2025.

Bata Shoe Advertisement . picryl.com/media/flashing-todays-styles-for-men-700536. Accessed 3 Sept. 2025.

Breward, Christopher, et al. The Cambridge Global History of Fashion: Volume 2. Cambridge University Press, 31 July 2023.

Contributors to Wikimedia projects. “Wikimedia Commons.” Wikimedia.org, Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., 7 Sept. 2004, commons.wikimedia.org/.

“Czech Fashion during the First Republic and the Protectorate.” Abczech.cz, 2025, www.abczech.cz/Czech-fashion-during-the-First-Republic-and-the-Protectorate-P7038755.html. Accessed 3 Sept. 2025.

DIY Conspiracy. “The History of Czechoslovak Punk.” DIY Conspiracy, 11 Jan. 2016, diyconspiracy.net/the-history-of-czechoslovakian-punk/. Accessed 3 Sept. 2025.

“Dum Mody Building .” Digital Photograph , commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:V%C3%A1clavsk%C3%A9_n%C3%A1m%C4%9Bst%C3%AD_58,_Krakovsk%C3%A1_26,_D%C5%AFm_m%C3%B3dy.jpg.

“File:2020-01-21 Freestyle Skiing – Snowboarding at the 2020 Winter Youth Olympics – Team Ski-Snowboard Cross – Quarterfinals – Quarterfinal 2 (Martin Rulsch) 37.Jpg - Wikimedia Commons.” Wikimedia.org, 21 Jan. 2020, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2020-01-21_Freestyle_skiing_%E2%80%93_Snowboarding_at_the_2020_Winter_Youth_Olympics_%E2%80%93_Team_Ski-Snowboard_Cross_%E2%80%93_Quarterfinals_%E2%80%93_Quarterfinal_2_(Martin_Rulsch)_37.jpg. Accessed 3 Sept. 2025.

“File:Diploma Selection 2041.Jpg - Wikimedia Commons.” Wikimedia.org, 9 Oct. 2021, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Diploma_Selection_2041.jpg. Accessed 3 Sept. 2025.

“File:Female Models on the Catwalk (Unsplash).Jpg - Wikimedia Commons.” Wikimedia.org, 14 Mar. 2016, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Female_models_on_the_catwalk_%28Unsplash%29.jpg. Accessed 3 Sept. 2025.

“File:Odběrnà Poukaz Do Tuzexu.jpg - Wikimedia Commons.” Wikimedia.org, 22 Mar. 2014, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Odb%C4%9Brn%C3%AD_poukaz_do_Tuzexu.jpg. Accessed 3 Sept. 2025.

“File:Soda Stereo 1984.Jpg - Wikimedia Commons.” Wikimedia.org, 17 Nov. 2015, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Soda_Stereo_1984.jpg. Accessed 3 Sept. 2025.

“File:Vysoká Škola Uměleckoprůmyslová v Praze.jpg - Wikimedia Commons.” Wikimedia.org, 16 June 2007, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vysok%C3%A1_%C5%A1kola_um%C4%9Bleckopr%C5%AFmyslov%C3%A1_v_Praze.jpg. Accessed 3 Sept. 2025.

“Fur Fashion Show in the Interconti, Frankfurt Am Main, 1978.” Wikimedia Commons , commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fur_fashion_show_in_the_Interconti,_Frankfurt_am_Main,_1978_%284%29.jpg.

“Fur Fashion Show in the Interconti, Frankfurt Am Main, 1978 .” Jpg, 13 Sept. 1978, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fur_fashion_show_in_the_Interconti,_Frankfurt_am_Main,_1978_(4).jpg.

Geering, Corinne. ““Is This Not Just Nationalism?” Disentangling the Threads of Folk Costumes in the History of Central and Eastern Europe.” Nationalities Papers, vol. 50, no. 4, 21 July 2021, pp. 1–20, https://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2021.21. Accessed 10 Feb. 2022.

“Jean Paul Gautier, Abito Haute Couture.” Wikimedia Commons , 2009, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jean_paul_gautier,_abito_haute_couture,_p-e_2009_%28amburgo,_museums_f%C3%BCr_kunst_und_gewebe%29.jpg.

Johnston, Raymond. “Did You Wear a “Rifle”? New Exhibit Looks Back at Jeans in 1980s Czechoslovakia.” @Expatscz, 30 May 2023, www.expats.cz/czech-news/article/did-you-wear-a-rifle-new-exhibit-looks-back-at-jeans-in-1980s-czechoslovakia. Accessed 3 Sept. 2025.

“Krása Kroje.” /, www.czechcenter.org/exhibit-kroj.

“Miss Czech-Slovak US Pageant.” Missczechslovakus.com, 2025, www.missczechslovakus.com/. Accessed 3 Sept. 2025.

Pixnio. “Free Picture: Snow, Downhill, Jump, Extreme Sport, Skiing, Winter, Adrenaline, Sport, Mountain.” Pixnio - Public Domain Images, 24 Oct. 2017, pixnio.com/sport/winter-sports/snow-downhill-jump-extreme-sport-skiing-winter-adrenaline-sport-mountain. Accessed 3 Sept. 2025.

“Prague Kolache Festival.” Praguekolachefestival.com, 2025, praguekolachefestival.com/history-of-the-kroj/. Accessed 3 Sept. 2025.

“Presentation of Czech Traditional Folk Clothing.” Mzv.gov.cz, 17 May 2022, mzv.gov.cz/washington/en/culture_events/news/presentation_of_czech_traditional_folk.html.

Uchalová, Eva. Czech Fashion 1918-1939. 1996.

Velinger, Jan. “Fashion behind the Iron Curtain: A New Book Explores How Czechoslovakia’s Communist Regime Used Fashion to Further Its Ideological Aims.” Radio Prague International, 27 Jan. 2017, english.radio.cz/fashion-behind-iron-curtain-a-new-book-explores-how-czechoslovakias-communist-8202276. Accessed 3 Sept. 2025.

Wikipedia Contributors. “Socialist Realism.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 25 Sept. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Socialist_realism.

Zuzana Vilikovská. “Fashion of Communist Era Exhibited.” Spectator.sme.sk, SME.sk, 2 May 2017, spectator.sme.sk/culture-and-lifestyle/c/fashion-of-communist-era-exhibited. Accessed 3 Sept. 2025.